Comparison of coupled and uncoupled currents during glutamate uptake by GLT-1 transporters

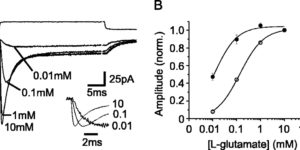

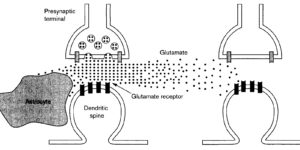

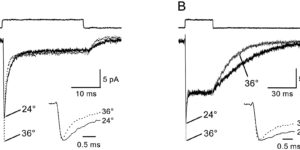

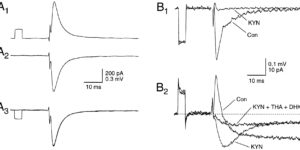

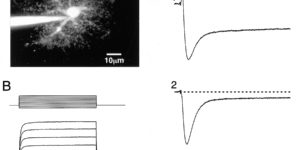

The transport of glutamate across the plasma membrane is coupled to the movement of cations (Na+, K+, and H+) that are necessary for glutamate uptake and transporter cycling as well as anions that are uncoupled from the flux of glutamate. Although the relationship between these coupled (stoichiometric) and uncoupled (anion) transporter currents is poorly understood, transporter-associated anion currents often are used to monitor transporter activity. To define the kinetic relationship between these two components, we have recorded transporter currents associated with stoichiometric and anion charge movements occurring in response to the rapid application of l-glutamate to outside-out patches from human embryonic kidney cells expressing GLT-1 transporters. Transporter-associated anion currents were approximately twice as slow to rise and decay as stoichiometric transport currents, but the presence of permeant anions did not slow transporter cycling. A kinetic model for GLT-1 was developed to simulate the behavior of both components of the transporter current and to estimate the capture efficiency of GLT-1. In this model the K+ counter-transport step was defined as rate-limiting, consistent with the slowing of transporter cycling after the substitution of internal K+ with Cs+ or Na+. The model predicts that in physiological conditions approximately 35% of GLT-1 transporters function as buffers, releasing glutamate back into the extracellular space after binding.