Glutamate transporters bring competition to the synapse

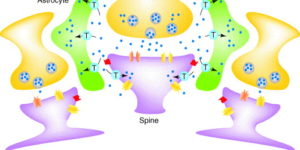

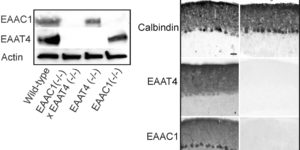

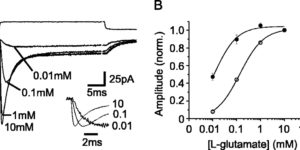

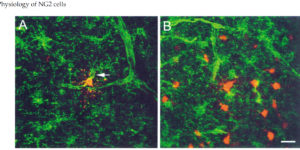

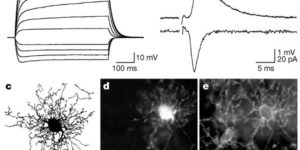

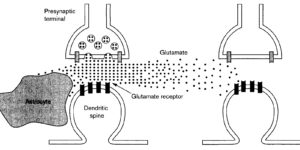

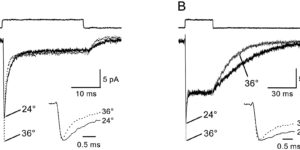

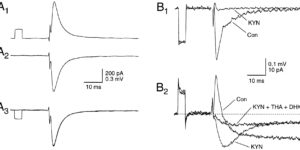

Glutamate transporters (GluTs) prevent the accumulation of glutamate and influence the occupancy of receptors at synapses. The ability of extrasynaptic NMDA receptors and metabotropic glutamate receptors to participate in signaling is tightly regulated by GluT activity. Astrocytes express the highest density of GluTs and dominate clearance away from these receptors; synapses that are not associated with astrocyte processes experience greater mGluR activation and can be exposed to glutamate released at adjacent synapses. Although less abundant, neuronal transporters residing in the postsynaptic membrane can also shield receptors from the glutamate that is released. The diversity in synaptic morphology suggests a correspondingly rich diversity of GluT function in excitatory transmission.